That sauce tray looks harmless, right? A few jars, a couple of squeeze bottles, maybe a ladle resting on the rim. But at busy street stalls, condiment stations can turn into a shared “touch point” where hands, utensils, and food all meet.

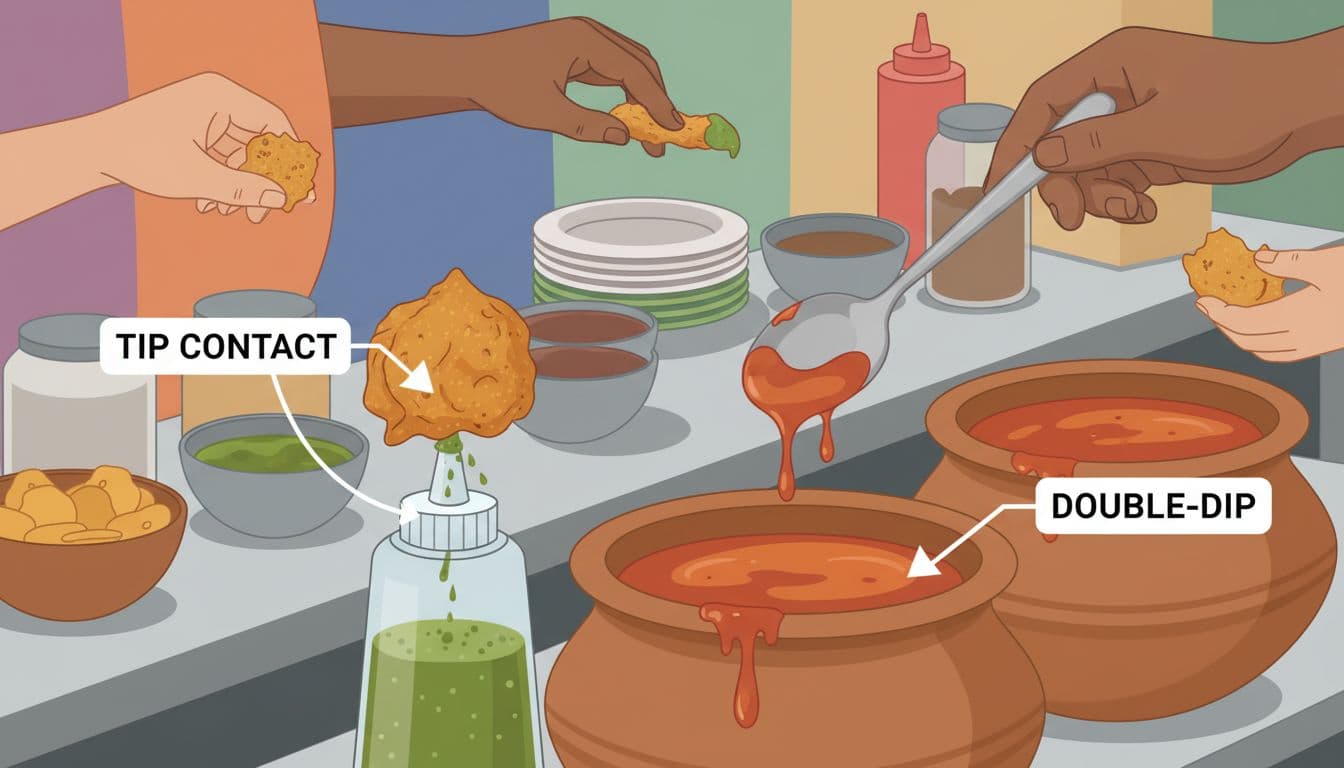

This guide is about condiment station hygiene in the real world, what to watch for in seconds, and how to avoid the biggest contamination patterns: shared ladles, squeeze tips touching food, and double-dipping. The goal isn’t to panic, it’s to eat smarter and keep the fun in street food.

Why condiment stations are the weak link (even at great stalls)

Most stalls cook food hot and fast, which helps reduce risk. The problem often starts after cooking, when sauces and toppings sit out and get used by dozens (or hundreds) of people.

Studies on street-vended foods repeatedly link contamination risk to handling habits, environmental exposure (dust, heat, flies), and how tools and surfaces are managed. If you want the research backdrop, this open-access review of street vendor practices is a useful reference: Food-handling practices linked to contamination in street foods. Another big-picture look at drivers like season and environment is here: Environmental and seasonal drivers of microbiological contamination in street-vended foods.

A condiment station is where small mistakes add up: one ladle shared across jars, one nozzle tapped on food, one spoon dipped after tasting. It’s like a public pen at a bank, except it’s going straight onto your lunch.

The 30-second scan: what clean looks like vs risky

You don’t need to inspect like an auditor. A quick visual scan tells you a lot.

Lower-risk setup usually has:

- Covered containers or lids between uses

- One utensil per sauce, not “one spoon for everything”

- Bottles that hover over food, not touch it

- A vendor handling sauce, rather than a customer free-for-all

Higher-risk setup often shows:

- Open jars with sauce splashed around the rim

- Ladles sitting inside sauce all day, with the handle touched by everyone

- Squeeze tips pressed onto food (or wiped with a reused rag)

- A “tasting spoon” that goes from mouth to pot

When the station looks messy, it often means the pace is winning over cleaning.

Shared ladles: the easiest contamination to spot

Shared-ladle contamination usually happens in three ways:

1) The handle is the real problem

The part people touch most is the handle. If customers serve themselves, that handle has been in many hands, then it goes back into the sauce or bangs against the rim.

What to look for: sticky buildup on handles, sauce crust near the grip, and fingerprints on the ladle shaft.

2) One utensil migrates between sauces

In a rush, a spoon meant for red chutney ends up in green chutney, then back again. Even if you don’t care about flavors mixing, it’s a sign the station isn’t controlled.

What to look for: ladles resting across multiple containers, or a single “community spoon” sitting on the table between jars.

3) Rim splatter and “resting ladles”

If a ladle lives in the jar, the jar rim becomes a smear zone. That’s where dust lands, hands touch, and drips collect.

Safer signs: a ladle stored in a clean cup (handle up), separate utensils per sauce, or the vendor portioning sauce from behind the counter.

Squeeze bottles: when the tip touches food, sauce can flow back

Squeeze bottles feel cleaner because they’re “closed.” But the nozzle is a choke point: it touches food, it gets wiped, then it goes right back over the next order.

The key issue: tip contact and backflow

When a nozzle presses into food (especially something hot, oily, or wet), it can pick up residue. With some bottles, pressure changes can pull tiny amounts back toward the tip. Even without true backflow, the nozzle surface becomes contaminated and spreads it.

What to look for:

- Tip touching fries, kebabs, chaat, or a bun

- A sauce “string” that snaps back onto the nozzle

- The vendor wiping the tip with a multi-use cloth that also wipes hands and counters

Cleaner habit: the bottle hovers above food and sauce falls by gravity, the nozzle never makes contact.

Double-dipping: it’s not just “gross,” it’s a pattern

Double-dipping at street stalls takes a few forms:

Customer double-dipping

Someone uses a spoon to taste, then dips again. Or they dunk a used skewer into a shared sauce pot. That’s high-contact sharing.

Vendor double-dipping

A vendor uses the same spoon to portion sauce, then uses it to stir, then portions again without a rinse. Even if hands are clean, the tool touches many surfaces and foods.

It’s worth separating two ideas: what’s “icky” and what’s high-risk. Some discussion around party dips suggests the danger is often overstated in certain settings, but the behavior still spreads saliva and germs in a shared dish. This overview captures that nuance: Double dipping: icky, not sicky. On street lines, the math changes because volume, heat, dust, and time at ambient temps can stack the odds.

If you want a broader safety lens across street vendors, this open-access review is a solid reference point: Factors influencing street-vended foods quality and safety.

How to order sauce with less risk (without acting weird about it)

Street food is social. You don’t want to police the stall, you just want to eat well. Try these low-friction moves:

Ask for sauce added by the vendor: It keeps hands off the station, and vendors often have a cleaner “service side.”

Choose cooked-to-order items: If the food is piping hot and sauced right away, you’re reducing time exposed to shared surfaces.

Skip communal garnish bins when they look handled: Chopped onions, cilantro, lemon wedges, and shredded cabbage can get grabbed repeatedly.

Prefer bottles over open jars, but watch the nozzle: A bottle used correctly can be cleaner than an open pot. A bottle used badly can be worse.

If you’re traveling with allergies, shared ladles and mixed jars also signal cross-contact risk. When the setup looks chaotic, that’s your cue to simplify the order.

At Street Food Blog, the best meals usually come from stalls that look calm under pressure: one person on the grill, one person assembling, and a tidy sauce routine that doesn’t rely on customers serving themselves.

Conclusion: trust the stall, but read the sauce station

A street stall can serve amazing food and still run a risky condiment corner. Watch for shared ladles, nozzle tips touching food, and any form of double-dipping, they’re the loudest signals in the shortest time. When the station looks controlled, covered, and utensil-separated, you can relax and enjoy the flavors. Next time you’re in line, take that quick scan before you sauce your plate.

Leave a Reply